For packet scheduling fairness?

Bufferbloat

TL;DR (Wikipedia):

Bufferbloat is a cause of high latency and jitter in packet-switched networks caused by excess buffering of packets. Bufferbloat can also cause packet delay variation (also known as jitter), as well as reduce the overall network throughput. When a router or switch is configured to use excessively large buffers, even very high-speed networks can become practically unusable for many interactive applications like voice over IP (VoIP), audio streaming, online gaming, and even ordinary web browsing.

Bufferbloat manifests as that annoying situation where one host in your home network hogs the router’s resources, leading to video feeds in calls starting to break up, or you’re starting to lag in an online game saying “oh fuck, forgot to close the torrents”.

Let’s break a packet’s journey down in two parts:

- host <-> home router and

- home router <-> bunch of other routers/middleboxes <-> destination

Due to how the internet is structured, we rely on ISPs’ equipment and all sorts of crappy middleboxes to route our packets to the destinations and their responses back to us (step 2 above). We have very little guarantees that they will get there. But that’s fine for the most part since there are protocols in the networking stack that provide such guarantees. What about latency though? How can we make sure latency is as low and consistent as possible?

Well, again most of the packet’s journey is out of our control. There is a great article series by Riot Games that describes what one can do (and by “one” I mean a billion-dollar company) to reduce latency for the home router <-> destination part as much as possible for the end-user.

But what about us, mortals?

As mentioned above bufferbloat occurs when the network is under load. It only

makes sense to figure out how our home router does packet scheduling.

Linux Queuing

Most of what we’re interested in lives in the tc (traffic control)

subsystem of the Linux kernel. There are several use cases for tc,

some of them being:

- Simulate network delays or packet loss

- Impose bandwidth limits

- Influence how packets are scheduled to provide QoS

tc maintains what’s called a qdisc -Queueing Discipline-

which concerns how the kernel will attempt to push

packets out to the network card. A dead simple example is: pfifo, no

processing is done, packets go out in a First-in First-out manner.

What’s the default algorithm for queuing then?

# root@router[~] → sysctl net.core.default_qdisc

net.core.default_qdisc = fq_codel

FQ-CoDel

FQ-CoDel or “Fair/Flow Queue CoDel” is based on three concepts:

- Monitoring of the minimum delay time packets spend sitting in a queue waiting to be sent out. If that delay rises above a threshold, then the algorithm starts dropping packets until the delay is back under the threshold.

- SFQ or “Stohastic Fair Queueing” dictates that traffic is split to buckets by computing the hash of the Source/Destination Address/Port and protocol (TCP/UDP) of the packet. On top of those buckets/queues we apply what’s described in (1). Then, the a packet in the next queue is selected in a round robin fashion.

- Sparse flow optimization: Priority is given to queues that recently went from inactive -> active state. This means that without any further configuration, the algorithm prioritizes latency-intensive traffic like DNS, SSH, VoIP etc.

fq_codel is very effective, while being a no-knobs kind of algorithm

that doesn’t involve complex and involved configuration on the user’s end. Hence

its adoption by most Linux distributions as the default qdisc.

Why would I want my router to drop packets?

How well does fq_codel work in practice? I ran the following test to figure this out:

- 2x iperf3 flows from host A to an iperf3 server on the internet

- 1x iperf3 flow from host B to another iperf3 server on the internet

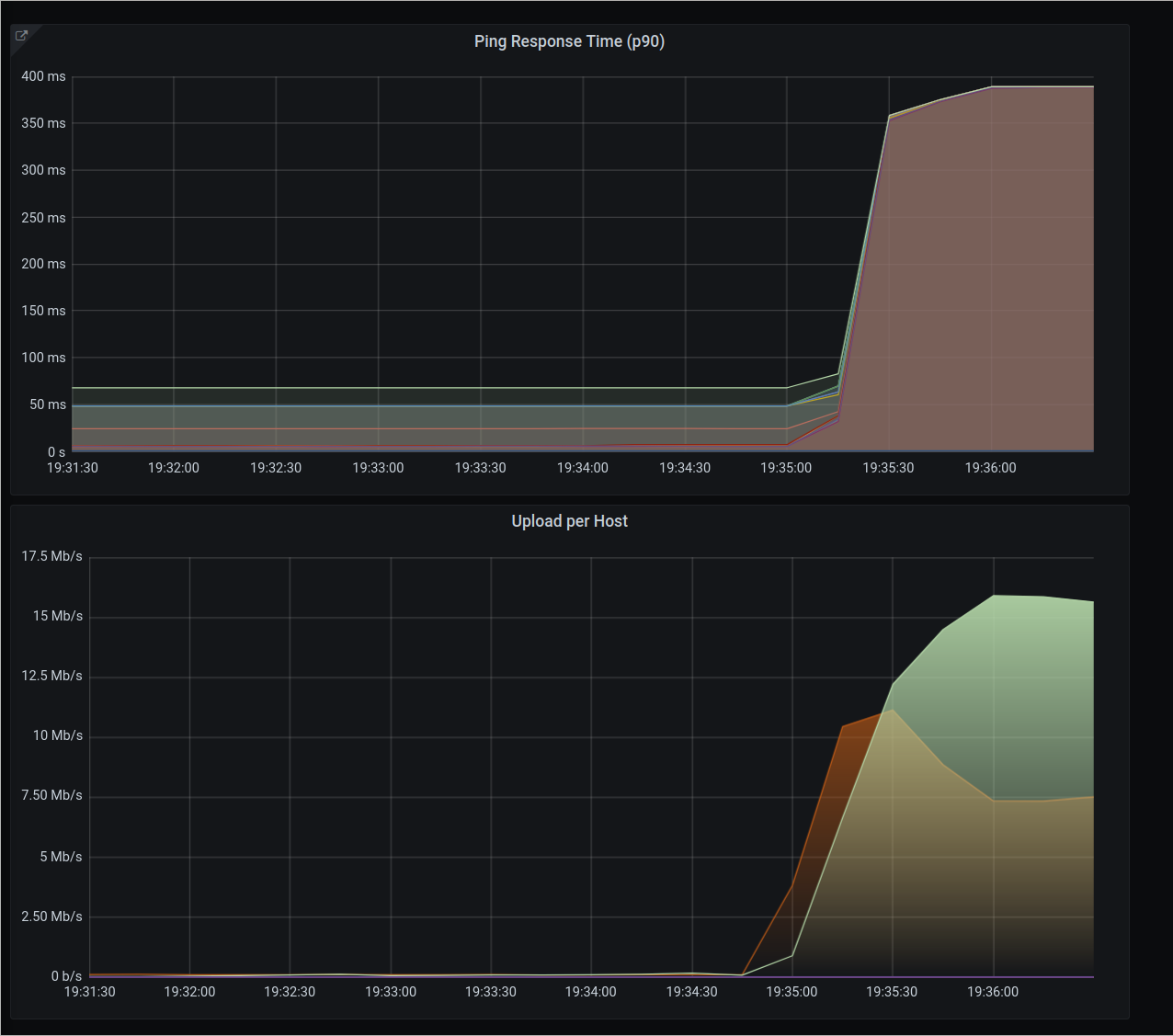

We can see the two main problems with fq_codel, in figure (1):

- There is no guarantee that each host will get its fair share of the bandwidth we manage. In this example, Host A gets 15Mbps, whereas Host B gets only 7Mbps.

- There’s ~350ms overhead added to all pings to various hosts around the internet. This is

bufferbloatat play.

Cake

Cake attempts to solve both of those issues (and more). It builds on its

predecessors such as fq_codel

and HTB, and in the same way as them, it

strives to be a works-great-by-default kind of algorithm. This eases deployment

and adoption as well.

Cake attempts to eliminate bufferbloat and provide fairness on several levels. The first one is IP-level flow fairness. There are three flow isolation modes that you can have:

- source address fairness

- destination address fairness

- “triple-isolate” mode

The first two are pretty self explanatory: the first ensures that no single address within a NAT’ed* network will hog the network with its traffic, and the same goes for the second for destination addresses. The last one considers both source and destination at the same time, and makes sure no source+destination pair will consume all the network resources.

Of course, this is a nice feature in order to avoid the first problem of IP fairness, but not all traffic requires the same treatment. A voice call will result in voice crackling if there’s latency. Similarly, a video call’s feed will start back-pressuring the server to drop the quality in order to avoid cutting the video feed altogether. Whereas having some latency spikes while streaming a video will just make buffering slower, but you probably won’t notice any difference. Then there’s torrents, which you mostly don’t care about, in terms of latency.

Cake splits traffic into tins. It uses an IP header field called TOS or DSCP

to categorize traffic to the corresponding tin. The TOS or Type Of Service is

supposed to indicate what kind of traffic the packet carries, but in reality it

never got widely deployed. Some of those tins are the following:

- Voice: any type of traffic that’s latency intensive

- Video: traffic like video call feed

- Bulk: e.g. torrents

- Best Effort: General type of traffic like browsing. We care about latency but not so much.

As mentioned above Cake’s defaults work great, but there is no bandwidth limit by default. Once we set the upload/download limits to 95% of the actual bandwidth the ISP provides, we’re good to go. Cake splits that bandwidth to the 4 tins mentioned above, with a predefined percentage (e.g. Voice gets 25% of the bandwidth). These are just soft limits, if there is no load on the network, other tins can grab the excess bandwidth.

Each tin has its own “target” latency in a predefined interval. In simple terms,

if a tin’s latency rises above the target latency, Cake will start pressuring

back flows by ECN marking on packets

or drop packets in order to ensure fairness and reduce the latency in tins with

higher priorities. Cake exposes

statistics on a) average, b) peak and c) base delay. All of those indicate how

much time a packet spent sitting in a queue until it was passed onto the networking stack.

Blah, does it work in practice?

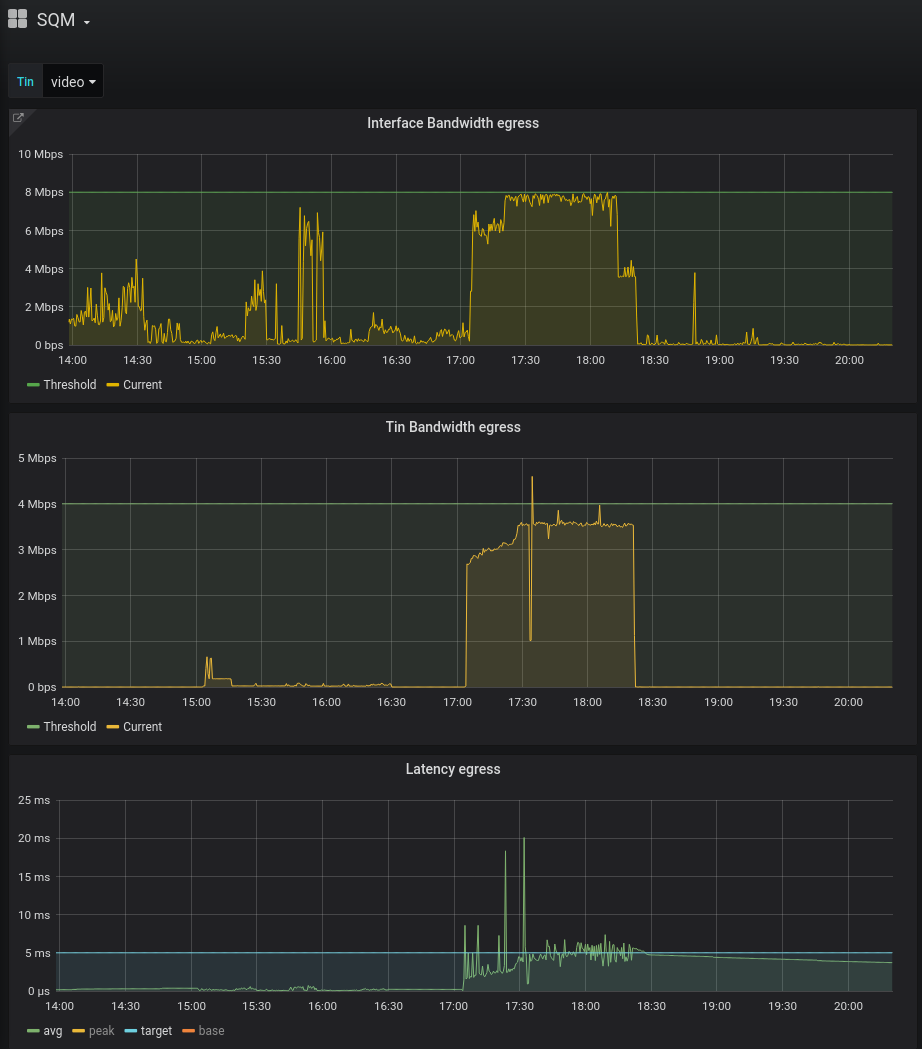

The second graph from the top shows the bandwidth for the specific tin we’re

looking at (video). On the last graph, we can see the average, target and peak

latencies.

With a target latency of 5ms, we can see that the average fluctuates around that

target (although there are some peaks above the limit) which looks very good!

We can see that out of the 8Mbps used by the interface, the video tin uses only 4Mbps.

How does the same latency graph look for the rest of the traffic?

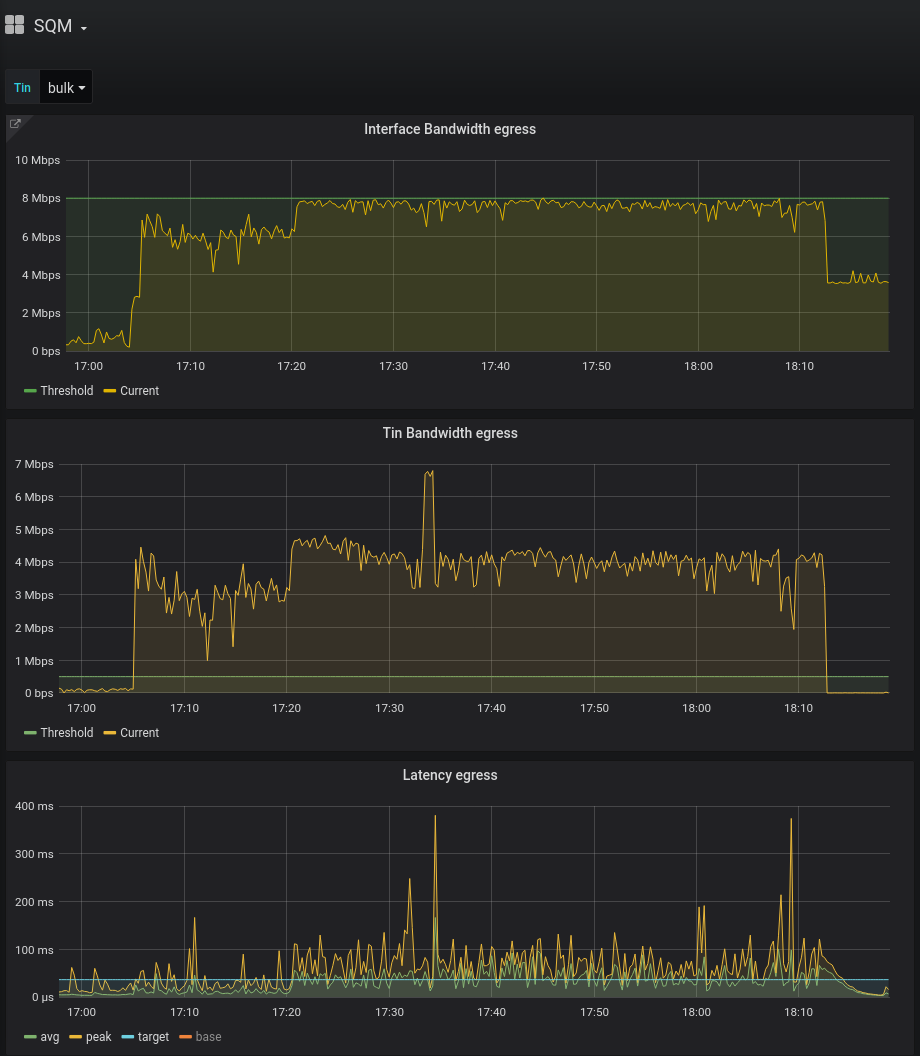

Things looks grim for the bulk traffic, with a target latency of 50ms, the

average flaps around that target.

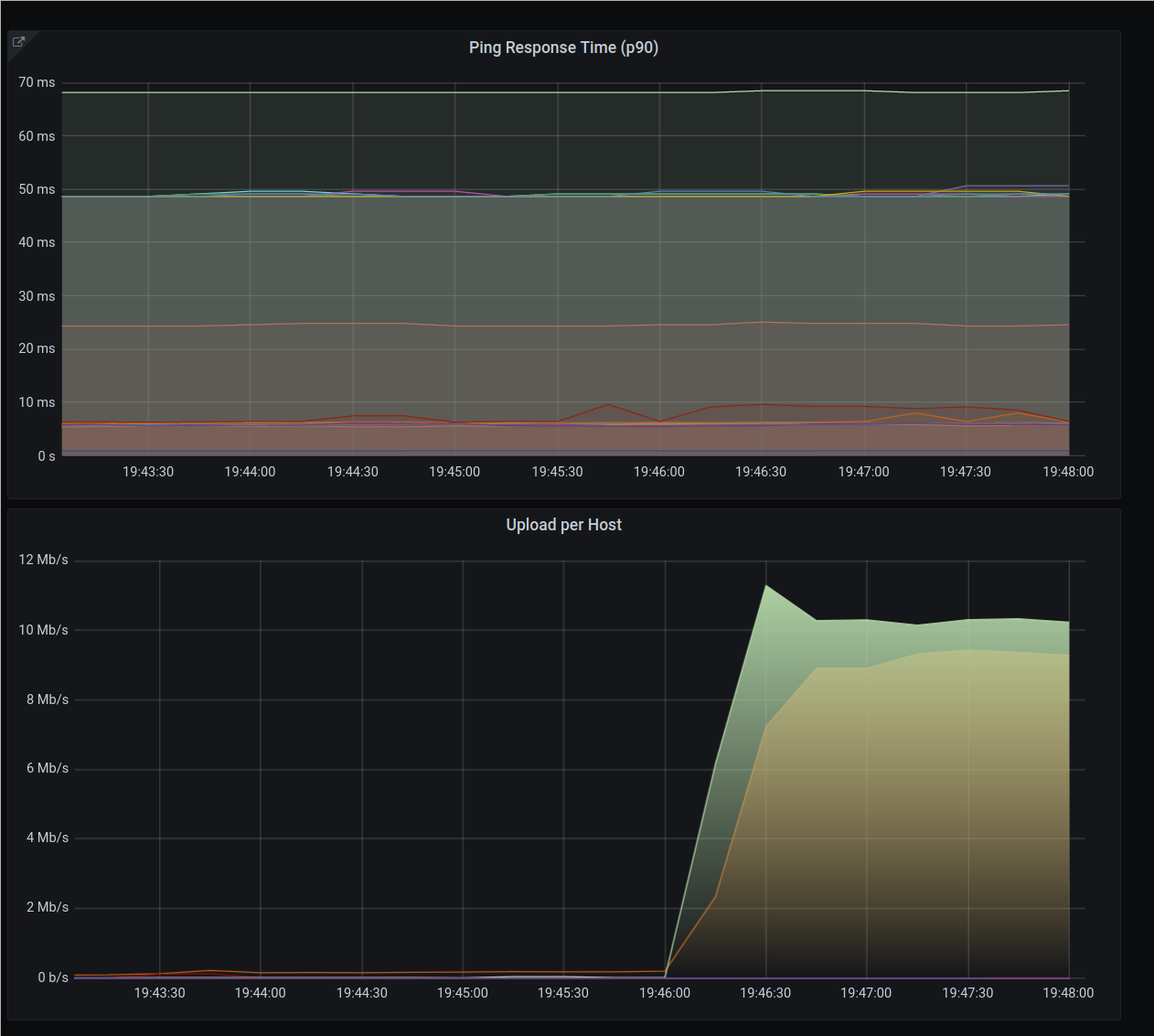

What about the IP level fairness issue shown above?

Again, two flows coming from host A (green) and one from host B (yellow). IP fairness is definitely better, both hosts hover ~9Mbps. As for latency, all flows seem unaffected by the uplink being congested.

But if DSCP is not widely used, what’s the use of Cake’s tins? Qosify!

Qosify is a package in OpenWRT (Linux-based OS targeting embedded devices) that uses an eBPF program to enable users to adjust packets’ DSCP field. I won’t go into details on how it works, but in principal, you can set DSCP field based on:

- Packet rate: For instance, if a flow’s pps rises above a threshold, you can

throw that flow in the

bulktin. - Domains: For example, throw all flows to

*.youtube.comto thebest_efforttin, ormeet.libreops.ccto thevideotin. - IP addresses: Same as above

- Ports: Move traffic to/from ports 22, 53, 123(NTP) etc to the

voicetin as those are latency intensive workloads.

There’s no magic here, but it lays the ground for

other things like writing eBPF programs to dynamically assign ToS/DSCP to flows that have

specific characteristics, e.g. monitor STUN/TURN requests for WebRTC, and add the

destination IP:port pairs to the voice tin.